Last month, I went to Alaska on vacation. Before I went,

nerd that I am, I scoped out where we were going and learned some remarkable

facts about the state. Alaska has more land mass than the next three largest

states of Texas, California and Montana combined. Alaska is so huge, if you superimposed

a map of the state onto the center of a map of the continental U.S., Alaska’s

Aleutian Islands would fall on San Diego in the west and the state’s eastern

islands would reach to Jacksonville, Florida, in the east. Alaska is so far

west, portions of its islands are technically in the eastern hemisphere. It has

more than 3,000 rivers and 3 million lakes. It is also the least-populated

state.

Last Christmas, I was given Kristin Hannah’s fantastic novel The Great Alone, which is set in Alaska during the 1970s, and it illustrates how remote the state is, how great the emptiness there is, so much so that it has a sinister aspect. I knew all that going in, but that is nothing compared to experiencing Alaska’s vastness and aloneness in person. We probably visited one percent of Alaska, but for the most part, we saw nothing but mile after mile of mountains and eerie desolation. While talking to residents, several emphasized that to survive an Alaskan winter, you must get into the sunlight and maintain social contact, or you could lose your mind or die.

For the last nearly two years, many of us have been living our own “Great Alone;” we’ve been isolated from one another, and that’s not good as the rising suicide rates and mental health issues have indicated. Many of us have started to venture out, but for others, the world is still a frightening place. I understand that; I used to suffer with anxiety. But I have a greater fear.

While we were in Alaska, my husband and I ziplined for the first time at Hoonah. It was billed as the tallest and highest zipline in the world. It sounded like a good idea when I booked it, but when we got there and saw how high up in the mountain the launch site was, I was thinking this may have been a mistake. It was a loooong way down.

We took the 45-minute bus ride up the mountain to the launch site, where we were dropped off to hike about a quarter mile down to the zipline site. On the way, we met a woman who was having some difficulty navigating the steep hill down to the site. We struck up a conversation and learned that she was 76, from rural Massachusetts, traveling alone because her husband had in her words “turned into an old curmudgeon and didn’t want to go anywhere,” and that she’d just had a hip replacement surgery in January.

The Launch Point at Hoonah, Icy Strait Point, Alaska

When I expressed that I was a little bit apprehensive about descending from what was equal to the height of the Empire State Building to the ground in 90 seconds at 60 miles an hour, she said not to be afraid, enjoy it. She’d ziplined six times in her life already.

I did enjoy the zipline. In fact, it was the highlight of the trip, and I’ve thought a lot about that woman since. She also told me that during the lockdown, she made 200 quilts for charity and intended to travel as long as she could, saying “I’m running out of time.”

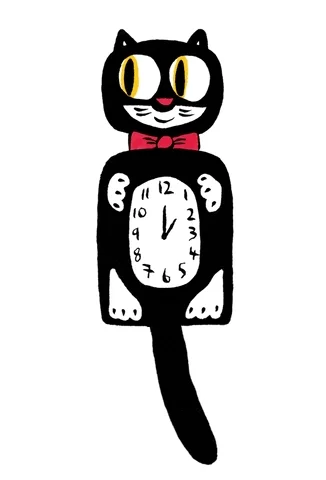

I know life can be scary; it always has been, and it always will be. But you can’t crawl in a hole and hide. That will kill you as well—maybe not physically, but it will kill that spark of life in you. We’re all running out of time. We’re all on the clock, and we don’t know how much time any of us have until the buzzer sounds. So, do what you can, take necessary precautions, evaluate the risks, but get out there and live. We’ve already lost so much; how much more can we afford to lose?

To me, the only scarier thing than dying, is not having

lived.

This article originally appeared in the October edition of Northern Connection magazine.

Great article!

ReplyDelete